Advocating for Yourself: My Epilepsy Journey

My name is Natalie, and I’ve been working with the Grand Rapids LGBTQ+ Healthcare Consortium since September 2024 as the Program Coordinator. Today is my last day with the Consortium — and since November is Epilepsy Awareness Month, I wanted to take this opportunity to share my own epilepsy journey.

When I was about 14 or 15, I started having seizures — though at the time, no one knew that’s what they were. It took nearly two years before I received a proper diagnosis.

Every single seizure was the same: I would put my hands around my throat and start making a choking noise. I never had the convulsions most people imagine when they hear the word “seizure.” Because of that, my episodes didn’t look like the “typical” kind you see in movies or on TV, which made it harder for my friends and my mom to understand what was happening — but it shouldn’t have been hard for a doctor to recognize.

One night, I was having a sleepover with a friend when she woke up because I was choking. She said I sat up, put my hands around my throat, and started making that same strange noise. She tried to wake me, but I wouldn’t respond. She ran to get my mom, and by the time they returned, the episode had stopped.

My mom took me to my pediatrician and explained what happened. Neither of us can remember exactly what was said at that appointment, but no treatment was recommended. Since it happened at night, the doctor referred us to a sleep clinic.

The sleep specialists asked my mom to try to capture one of the episodes on video. So she started sleeping next to me, and whenever I’d have an episode, she’d grab her phone and try to record it. Of course, it was the middle of the night and she was half asleep — so she was never able to get a clear video. She was convinced they were seizures, but the clinic wasn’t sure and ordered a sleep study.

During the sleep study, I had another episode. The sleep doctor, however, did not recognize it as a seizure. Instead, he diagnosed me with sleep apnea, despite my mom’s concerns. I was prescribed a CPAP machine, but because it was a misdiagnosis, the episodes didn’t stop.

At that time, I also wasn’t getting good sleep — because, as we later learned, I was having seizures almost every night. I was exhausted, confused, and frustrated, and no one could tell us why. It was an incredibly difficult time. The seizures kept happening night after night while my mom was repeatedly told it was just sleep apnea.

When I was 17, I started having seizures during the day. The same thing would happen, but now I was awake beforehand. The first daytime seizure happened at school. A group of kids helped me to the office, where the staff called my mom. (I have no memory of this — I was in class one minute, and the next, I was in the front office with my mom sitting next to me asking if I was okay.) She came to pick me up and took me straight to the pediatrician.

On the way, I had another seizure in the car. Then, once we got to the doctor’s office, I had yet another one — right in front of him. He immediately said, “That’s a seizure.” Finally, I was referred to a neurologist.

After an EEG and a hospital stay, I was officially diagnosed with focal epilepsy. I had been having left temporal lobe focal seizures every single night for nearly two years. The neurologists couldn’t believe the sleep doctor had thought it was sleep apnea — to them, it was clearly a seizure disorder.

They started me on medication, and since the day I was diagnosed, I haven’t had a seizure.

I’m 28 now and have been seizure-free for over 11 years. While I still experience a few side effects, epilepsy does not define my daily life.

If there’s one thing I’ve learned from my journey, it’s this: always advocate for yourself.

At the time, I couldn’t — I was under 18 and had no memory of my seizures. My mom did everything she could, even when she was told over and over that she was wrong. She knew something wasn’t right and never stopped pushing for answers.

Your doctor may be an expert, but you are the expert on your own body. Don’t be afraid to speak up, ask questions, or seek a second opinion. You deserve to be heard, believed, and cared for.

The Importance of Black People within the LGBTQ+ Community: A Tribute to Pioneers and Activists

In honor of Black History Month, this blog post celebrates the essential role Black individuals have played in shaping the LGBTQ+ community. Despite facing the dual challenges of racial and gender or sexual discrimination, Black people have been at the forefront of the fight for civil rights, social justice, and LGBTQ+ equality. Their impact, from the pioneering work of Black trans women to the contributions of Black LGBTQ+ activists, has been foundational in the progress we see today.

While the LGBTQ+ rights movement has always intersected with issues of race and identity, the contributions of Black people—especially Black trans women—are often overlooked in mainstream history. These trailblazers have not only shaped LGBTQ+ advocacy but have provided vital leadership and resilience that continue to influence the movement. This post highlights the rich history of Black LGBTQ+ figures whose activism and leadership have left an indelible mark on the community.

Historical Context: Intersectionality in the LGBTQ+ Movement

The fight for LGBTQ+ rights has always been deeply intertwined with the struggle for racial justice. Black LGBTQ+ individuals have faced a unique set of challenges due to their race and sexual or gender identities. For many years, this intersectionality has meant being excluded from both mainstream LGBTQ+ spaces and traditional civil rights movements. Yet, it is these very individuals who have helped define and strengthen the movement we see today. The contributions of Black LGBTQ+ people, especially those at the intersections of race, gender, and sexuality, have been crucial to advancing both civil and human rights.

Pioneers in the LGBTQ+ Rights Movement: The Foundational Figures

One of the most pivotal moments in LGBTQ+ history was the 1969 Stonewall Riots. While Marsha P. Johnson and Sylvia Rivera are often celebrated as foundational figures in this movement, it is essential to recognize the broader scope of Black LGBTQ+ contributions to the fight for equality.

Marsha P. Johnson: A Revolutionary Figure

Marsha P. Johnson, a Black trans woman and drag queen, was one of the most important figures in the Stonewall Riots. Along with Sylvia Rivera, she co-founded the Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries (STAR), an organization dedicated to advocating for homeless queer and trans people. Marsha’s leadership, particularly in pushing for the inclusion of marginalized groups within the LGBTQ+ movement, helped to lay the foundation for modern-day trans activism.

Her advocacy didn’t just influence the rights of transgender individuals—it reshaped the way we think about intersectional activism, where race, gender, and sexual identity are all part of the fight for justice and equality.

Sylvia Rivera: A Fierce Ally and Advocate

Sylvia Rivera, an LGBTQ+ rights activist, also played a crucial role in the early LGBTQ+ rights movement. Alongside Marsha, she worked tirelessly to create spaces for marginalized communities, particularly trans and queer people of color, who had long been excluded from the larger LGBTQ+ movement. Despite facing significant opposition from within the movement itself, Sylvia’s commitment to trans and queer inclusion made her a key figure in ensuring the voices of the most marginalized were heard.

Rivera’s legacy as an advocate for trans rights and inclusivity continues to inspire those who fight for visibility and equality today.

Additional Pioneers Who Shaped the Movement

Beyond Johnson and Rivera, many other Black LGBTQ+ figures have made significant contributions to the struggle for rights and recognition. These activists laid the groundwork for the fight for LGBTQ+ liberation we continue to carry on today.

Bayard Rustin: A Civil Rights and LGBTQ+ Leader

Bayard Rustin (1912–1987), a civil rights strategist and one of the principal organizers of the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, was instrumental in shaping the civil rights movement. Though Rustin was openly gay, his sexuality was often overlooked or downplayed within mainstream civil rights spaces. Nevertheless, he made a lasting impact by advocating for both racial and LGBTQ+ equality, proving that these struggles are deeply interconnected. In 2019, the movie Rustin was released, focusing on his life and legacy, highlighting his pivotal role in the movement and his resilience in the face of discrimination. The film brought renewed attention to Rustin’s contributions and the intersectionality of his activism, celebrating his courage and the complexity of his identity as a Black gay man who helped shape one of the most significant moments in American history.

Frances Thompson: A Trailblazer for Black LGBTQ+ Rights

Frances Thompson (1857-1925) was a pioneering Black trans activist, is thought to be the first trans woman to testify before Congress, advocating for the rights and dignity of transgender individuals. Born into slavery in the 1850s, Thompson’s life spanned eras of immense social change, and her courage in publicly embracing her identity during times of racial and gender discrimination made her a crucial figure in both the Black and LGBTQ+ rights movements. Her testimony before Congress helped highlight the unique challenges faced by Black transgender individuals, ensuring intersectionality was central to the fight for justice. Though often overlooked, Thompson's legacy continues to inspire those working toward equality today.

Audre Lorde: Poet, Feminist, and Revolutionary

Audre Lorde (1934–1992) was a Black lesbian poet and activist whose work focused on the intersections of race, gender, and sexuality. Lorde’s poetry, essays, and activism challenged societal norms and called for radical self-love and inclusion. Through her writing, she emphasized the importance of addressing both the visible and invisible aspects of identity—how race, gender, and sexuality all converge to shape our experiences.

Her work continues to influence both feminist and LGBTQ+ movements, providing a blueprint for those who seek to build an inclusive world for all people.

James Baldwin: A Literary Giant

James Baldwin (1924–1987) was a novelist, essayist, and playwright whose work explored the complexities of race, sexuality, and identity in America. Baldwin’s personal exploration of his queer identity and his profound insights into the Black experience in America made him a pivotal figure in both the LGBTQ+ and civil rights movements.

Baldwin’s eloquent writing challenged societal norms and sparked important conversations about the intersections of race, gender, and sexuality. His influence endures, and his work continues to inspire activists and writers today.

Black LGBTQ+ Activism Today: Continuing the Fight

The LGBTQ+ movement continues to be shaped by the work of Black activists who carry forward the legacies of those who came before them. Figures such as Brittney Griner, Raquel Willis, Laverne Cox, and Billy Porter are among those raising awareness on crucial issues like police brutality, access to healthcare, and the rights of LGBTQ+ youth.

Laverne Cox: A Groundbreaking Advocate for Black Trans Visibility

Laverne Cox, a groundbreaking actress and advocate, has used her platform to amplify the visibility of Black trans women and challenge harmful stereotypes about transgender people. As the first openly transgender woman of color nominated for a Primetime Emmy Award, Cox has been instrumental in reshaping how trans individuals—particularly trans people of color—are portrayed in mainstream media. Her advocacy extends beyond acting, as she continues to be a fierce voice for trans rights and inclusion in all aspects of society.

Brittney Griner: A Symbol of Resilience and Advocacy

Brittney Griner, the WNBA star who became a symbol of resilience after her wrongful detention in Russia, has also been an advocate for both racial justice and LGBTQ+ rights. Griner's public journey has highlighted the intersections of race, gender, and sexuality, emphasizing the need for solidarity across movements. As a Black queer woman, Griner’s courage has empowered others to speak out about issues related to justice, equality, and the rights of LGBTQ+ people.

Raquel Willis: Amplifying Black Trans Voices

Raquel Willis, a Black trans activist and writer, has been a fierce advocate for the rights and visibility of Black trans individuals. Through her work, she has shed light on the unique challenges faced by Black trans people, particularly around issues of safety, healthcare, and justice. Willis’s advocacy emphasizes the importance of centering the voices of Black trans people in broader conversations about LGBTQ+ rights and inclusion.

Billy Porter: Breaking Barriers in Fashion and Entertainment

Billy Porter, a renowned actor and fashion icon, has shattered expectations with his bold approach to gender expression. Through his roles, activism, and public appearances, Porter has become an advocate for Black queer people, championing their representation and inclusion in the entertainment industry and beyond. His fearless exploration of fashion and gender norms has made him a powerful figure in reshaping how the world views Black LGBTQ+ individuals.

Conclusion: Honoring the Legacy of Black LGBTQ+ Pioneers

The contributions of Black LGBTQ+ individuals—both past and present—have been instrumental in shaping the ongoing fight for equality. From the groundbreaking work of Marsha P. Johnson and Sylvia Rivera to the literary brilliance of James Baldwin and Audre Lorde, these pioneers have paved the way for generations of LGBTQ+ activists. Today, figures like Billy Porter, and Brittney Griner continue to push boundaries and advocate for justice, visibility, and inclusion. Their commitment to justice and the ongoing fight for LGBTQ+ liberation continues to inspire movements today, reminding us that the struggle for liberation is a collective one.

As we continue to move forward, it’s essential to honor and uplift the voices of Black LGBTQ+ individuals, ensuring that their legacies are preserved and their contributions are never forgotten. Their activism and courage have shaped the LGBTQ+ movement into what it is today, and their work is far from finished.

Let’s celebrate and continue to amplify the voices of Black LGBTQ+ leaders who continue to fight for a more inclusive, just, and equal world for all.

Resources

Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries(STAR) Manifesto

Audre Lorde Books and Writings

navigating the holidays as an lgbtq+ person

While the holiday season can be a time of celebration and joy, it’s also a period that can bring heightened emotions, stress, and discomfort, especially for members of the LGBTQ+ community. Although research shows no significant spike in mental health struggles during the holidays, existing conditions may be exacerbated, particularly for individuals without supportive family or a safe network.

A 2014 survey by the National Alliance on Mental Illness revealed that 64% of people with mental health challenges report that the holiday season makes their conditions worse. For 24% of people, the "holiday blues" make things significantly harder. These heightened emotional experiences are even more relevant for LGBTQ+ individuals, who face a higher risk of mental health conditions compared to heterosexual people. According to the National Survey on Drug Use and Health, lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults are more than twice as likely to experience mental health struggles, while transgender people are nearly four times as likely to face such challenges.

So, let’s talk about the struggles this community faces and some tips for those who may need extra support.

5 Common Holiday Challenges for LGBTQ+ Individuals

Lack of Acceptance: Some LGBTQ+ individuals may still be in the process of coming out or have faced rejection in the past. Returning home can stir up painful memories, triggering feelings of shame and guilt.

Microaggressions: Family members, even if well-intentioned, may make subtle or unintentional comments that are offensive or dismissive of LGBTQ+ identities. These microaggressions can be hurtful and add to the discomfort of an unsupportive family environment.

Misgendering/Deadnaming: For transgender and non-binary individuals, the holidays may bring repeated misgendering or deadnaming from family members who don't understand or respect their gender identity or chosen name. This can feel deeply invalidating and damaging.

Isolation: Not all LGBTQ+ individuals have supportive or accepting social networks. For those estranged from their families or with limited community connections, the holidays can highlight feelings of loneliness.

Mental Health Struggles: Feelings of anxiety, depression, and isolation can become more intense during the holiday season, particularly for those already dealing with stigma or discrimination.

5 Strategies for Nurturing Mental Health and Creating Safe Spaces

Although the holiday season can be challenging, there are ways to protect your mental health and create a sense of safety. Here are some tips to help:

Reflect on Your Needs and Set Boundaries: Before heading home, take time to reflect on what you want from the holiday season and what you need to avoid. Setting boundaries is essential. It’s important to communicate your needs for respect and understanding, especially when sensitive topics arise. You have the right to feel safe and accepted.

Build a Supportive Community: If your family isn't supportive, it's vital to connect with others who affirm your identity. Consider organizing get-togethers with trusted friends, or chosen family.

Create Safe Spaces at Home: For those who didn’t grow up in supportive households, creating your own sanctuary at home is vital for mental health and healing. Remember: your home should be a place where you can rest, recharge and feel valued.

Practice Self-Care: Make time for activities that nurture your mental health. Self-care can help you stay grounded during stressful times. Treat yourself! You deserve it!

Take Breaks and Manage Stress: It’s okay to step away from situations that feel overwhelming. Simple techniques like deep breathing, taking short walks, or visualizing a peaceful place can help reduce anxiety and stress.

Moving Forward

It’s important to acknowledge that many LGBTQ+ people face systemic challenges throughout the year, but the holiday season often magnifies these struggles. For those who might not feel safe or affirmed in their families, the holiday season can be a reminder of what is lacking, but also of what can be built. We can create our own families of choice, our own affirming spaces, and our own traditions of love and support. If you’re struggling, please know that you’re not alone, and resources like The Trevor Project are always available to provide support and guidance.

The holiday season should be a time of joy, and although it may not always feel that way, we can create the space for peace, love, and authenticity — for ourselves and for those who share our journey.

If you are struggling this season don’t hesitate to reach out for help! There are so many people who want what’s best for you and who are there for you 24/7. Check out the resources linked below.

Resources

The Trevor Project: (866) 488-7386

The LGBT National Hotline: (888) 843-4564, 1 on 1 Peer Support Chat

The Transgender Crisis Hotline: (877) 565-8860

National Suicide Prevention Lifeline: 988

Understanding Trans Lives: A Deep Dive for Transgender Awareness Week

Transgender Awareness Week is an important time for reflection, recognition, and advocacy within the transgender community and among allies. This week is not only about celebrating the accomplishments of transgender individuals but also to amplify their voices and highlight the unique challenges they face.

Understanding Transgender Identity

Being transgender refers to individuals whose gender identity differs from the sex they were assigned at birth. This identity exists independently of biological sex and often comes with a desire to transition to the gender that aligns with their true selves, the gender they identify with. Transgender people may identify as female, male, nonbinary, gender non-conforming, or embrace other gender identities that differ from the traditional binary framework. It’s essential to recognize that being transgender is about authenticity and self-recognition, reflecting a diverse spectrum of experiences and expressions within the entire human experience. Understanding and respecting these identities is important when it comes to fostering acceptance, affirmation, and inclusivity in our communities.

The Origins of Transgender Awareness Week

Transgender Awareness Week is an annual event that began in 2017 with the aim of highlighting the challenges faced by transgender individuals. Established to celebrate the achievements, talents, and contributions of transgender people globally, the week serves as a platform for advocacy and education. It takes place in November, strategically coinciding with Transgender Day of Remembrance, which honors the lives lost to transphobia and violence. This alignment underscores the dual purpose of the week: to recognize the resilience of the transgender community while also acknowledging the urgent need for social change and justice. Through awareness and activism, Transgender Awareness Week continues to foster greater understanding of gender diversity.

Recognizing Accomplishments

Throughout history, transgender individuals have made significant contributions to society in various fields, including art, science, politics, and activism. Transgender Awareness Week provides an opportunity to shine a light on these achievements, honoring those who have paved the way for greater acceptance and understanding. By sharing stories of success, we inspire others and demonstrate the resilience and strength of the transgender community.

Promoting Visibility

Visibility is a powerful tool in combating prejudice and discrimination. Transgender Awareness Week encourages everyone—transgender individuals and allies alike—to engage in conversations about gender identity and expression. Increased visibility helps normalize transgender experiences and fosters a sense of belonging. When people see diverse representations of gender in media, workplaces, and communities, it helps to challenge stereotypes and misconceptions.

Educating on Rights Issues

Education is at the heart of Transgender Awareness Week. Many people still lack a clear understanding of transgender rights and the specific issues faced by this community. From healthcare access and legal recognition to workplace discrimination and violence, the challenges are significant. By providing information and resources, we can empower individuals to advocate for change and support transgender rights.

Taking Action

As we observe Transgender Awareness Week, let us commit to being allies in this journey. Whether it’s attending events, engaging in educational activities, or simply listening to and uplifting transgender voices, every action counts. We can work to create a more inclusive world where everyone, regardless of their gender identity, can thrive.

What is Transgender Day of Remembrance?

Transgender Day of Remembrance (TDOR) is a poignant observance established in 1999 by transgender advocate Gwendolyn Ann Smith. It began as a vigil to honor Rita Hester, a transgender woman tragically murdered in 1998. This vigil aimed to commemorate not only Rita but also all transgender individuals who have lost their lives to violence, highlighting the systemic issues and prejudice faced by the transgender community. Over the years, TDOR has evolved into a powerful annual event that fosters remembrance, awareness, and advocacy, bringing people together to honor the lives taken and to reinforce the need for continued action against anti-transgender violence and discrimination. Each year, communities across the globe gather to reflect, mourn, and commit to creating a safer, more inclusive world for all.

“Transgender Day of Remembrance seeks to highlight the losses we face due to anti-transgender bigotry and violence. I am no stranger to the need to fight for our rights, and the right to simply exist is first and foremost. With so many seeking to erase transgender people — sometimes in the most brutal ways possible — it is vitally important that those we lose are remembered, and that we continue to fight for justice.”

– Gwendolyn Ann Smith (Transgender Day of Remembrance founder)

Transgender Day of Remembrance 2024

Listed below are the names of the 28 transgender individuals (that we know of) who have been tragically killed in the US in 2024 (as of 10/25/24). Click on each name to learn more about each of their lives and the circumstances of their deaths. We must continue to say their names and share their stories to ensure they are never forgotten. We must also advocate for change to help prevent these acts of violence from happening in the future.

(Content Warning: These articles contain discussions of violence against and details surrounding the deaths of transgender individuals.)

Kitty Monroe(43)-Sasha Williams(36)-África Parrilla García(25)-Righteous Torrence “TK” Hill(35)-Reyna Hernandez(54)-Diamond Brigman(36)- Alex “Boo” Taylor Franco(21)-Meraxes Medina(24)-Yella Clark(45)-River Nevaeh Goddard(17)-Tee “Lagend Billions” Arnold(36)-Starr Brown-Andrea Doria Dos Passos(37)-Kita Bee(46)-Jazlynn Johnson(18)-Tayy Dior Thomas(17)- Michelle Henry(25)-Liara Kaylee Tsai(35)-Pauly Likens(14)-Kenji Spurgeon(23)-Shannon Boswell(30)-Monique Brooks(49)-Dylan Gurley(20)-Tai’Von Lathan(24)- Kassim Omar(29)-Redd(25)-Honee Daniels(37)-Nex Benedict(16)

Resources

How to be an Ally to Transgender and Nonbinary Youth

What does it mean to “come out”?

October 11th was National Coming Out Day! Let’s talk about what it means to come out and what it means when a loved one comes out to you. Coming out is a significant and often transformative process for those who identify as LGBTQ+. At its core, coming out refers to the journey of acknowledging and accepting one’s sexual orientation or gender identity and then sharing that identity with others. This act can range from a deeply personal revelation to a public declaration, and it’s important to understand that each individual’s experience is unique. You might have encountered discussions about “coming out” that seem overly simplistic, judgmental, or even intimidating. The reality is that there isn’t a single way to come out or live openly. There may be some individuals in our lives with whom we wish to share our sexual orientation or gender identity, while there are others with whom we might not feel safe or comfortable disclosing that information. And that’s completely fine!

A Personal Journey

Coming out is not just a single event; lots of folks find themselves coming out many times to many different people, whether it's sharing your identity with a close friend online, confiding in a family member, or telling a partner; it's a multifaceted journey that can evoke a wide array of emotions. Many people feel a mix of fear and anxiety, but also relief and elation as they embrace their true selves. The courage it takes to come out cannot be overstated; it often involves vulnerability and a deep introspection about one’s identity.

The Process of Coming Out

For most, the first step in coming out is acknowledging one’s identity to oneself. This self-acceptance is crucial, as it lays the foundation for sharing that identity with others. After this internal recognition, the next steps often involve sharing with close friends, family, and community members. The timing and method of coming out vary greatly; some may choose to do so quickly, while others take their time.

Navigating Risks and Rewards

Deciding to come out is a highly personal choice that must consider various factors. While coming out can foster deeper connections and a sense of freedom, it also carries risks. Individuals may face potential backlash, emotional upheaval, or even physical danger, depending on their environment and the people in their lives.

Before coming out, it’s vital to weigh the potential consequences. Questions to consider include: Will coming out jeopardize your emotional or financial support from loved ones? Is there a risk of physical harm? Are you facing pressure to conform to expectations? If the answers to these questions lean toward concern, it may be wise to wait or seek additional support before taking this step.

Empowering Your Experience

Ultimately, the decision to come out is yours alone. You have the power to choose how, when, and with whom to share your identity. Many find it helpful to start this journey within supportive communities, whether that be through LGBTQ+ groups, online forums, or trusted friends. Surrounding yourself with understanding individuals can provide the comfort and encouragement needed to navigate this path.

Coming out is a personal journey that can bring immense growth and connection, but it’s also one that should be approached with care and consideration. Remember, you are in charge of your narrative, and your journey is valid—no matter how it unfolds.

What to say/do when someone comes out to you

Your response should depend on your relationship with the person, but there are some universally supportive actions you can take.

Thank Them- Express your appreciation for their trust by saying something like, “Thank you for sharing this with me.” It is a meaningful gift when someone feels confident enough to confide in you. You can also check in on how they feel about sharing this part of their identity.

Ask About Pronouns- If someone comes out as transgender, nonbinary, or gender-diverse, ask which pronouns they use. Use “use” rather than “prefer,” as the latter implies that correct pronoun usage is optional rather than essential. Pro-tip: It’s helpful to ask people about their pronouns in everyday situations, not just after they come out. Sharing your own pronouns can also create an inclusive environment.

Show Support- Inquire about how they would like to be supported, as some may want ongoing support while others prefer to move on. Remember not to act surprised, as this can imply that you didn’t consider their queerness or trans identity as a possibility. It’s also okay to ask about their coming out journey and what it has been like for them, but don’t get offended if they do not want to elaborate.

Offer Them a Way Out- If you want to ask about their identity, ensure they know they aren’t obligated to answer. Phrases like, “Is it okay if I ask you about this?” can help. Providing context for your questions can also be beneficial—for instance, explaining your interest based on a similar experience, while remembering not to make it about you.

Use Ring Theory- If you’re grappling with emotions about someone’s coming out, it’s important not to place that burden on them.

What NOT to say/do when someone comes out to you

Avoid Outing- When someone confides in you about their LGBTQ+ identity, never share that information with others without their explicit permission. Respect their right to control their own narrative, as outing someone can have serious repercussions in their personal and professional lives. Instead, aim to be a confidential and safe person for them, recognizing that coming out is a deeply personal choice and that being entrusted with this information is a privilege.

Respect Privacy- Don’t pry into details that haven’t been voluntarily shared. Maintain a respectful distance regarding their journey unless they invite you in. Avoid overly personal questions that might make them uncomfortable. Allow them to share at their own pace, try using open-ended questions such as, “Would you like to share more about how you’re feeling?” This approach empowers them to control their narrative while ensuring they feel supported.

Focus on Identity, Not Sexuality- Keep the conversation centered on their identity rather than sexual preferences or activities. Coming out is about identity, not just sexuality. Recognizing that sexual orientation and gender identity are fundamental to a person’s sense of self helps create a respectful and affirming environment.

Don’t Dismiss Their Experience- Avoid minimizing their journey with comments that suggest “it’s just a phase” or “that you always knew”. Such remarks can be dismissive and belittling. Instead, acknowledge the significance of their disclosure and affirm their feelings. Show genuine curiosity and empathy, asking how you can best support them during this time.

Steer Clear of Negativity- Even if you’re struggling with the news, refrain from expressing doubts or negative feelings in response to their coming out. Manage your emotions privately and don’t impose them on the person who is sharing with you. If needed, seek support from other allies or professionals to process your feelings, ensuring that you prioritize the emotional safety and well-being of the person who has confided in you, it most likely wasn't easy for them.

“Coming Out?” vs. “Letting In?”

Letting in is an intentional act—a way to invite others into our inner world. It’s about choosing whom to share our truth with, rather than feeling pressured to present a polished narrative of our identities. This process acknowledges that our experiences are complex and can't always be put into simple statements or singular moments. When we let others in, we exercise the power of choice. It’s a way to engage in meaningful relationships, allowing us to decide who deserves a glimpse of our authentic selves. This choice empowers us, giving us agency over our stories and how we share them. Opening up can profoundly affect our lives. It has the potential to foster closer relationships and build trust. Yet, we must weigh this against the risks involved. Being selective about whom we let in can protect us while still allowing us to cultivate meaningful connections.Ultimately, letting in is about creating space for ourselves and others. It’s an invitation to explore the complexities of our identities and relationships. By choosing to let in those who align with our needs for safety and comfort, we embark on a journey of authentic connection, one shared moment at a time.

Resources

Parents: Tips for supporting your LGBTQ+ child and yourself during the coming-out process

The Coming out Handbook- The Trevor Project

“Coming Out?” or “Letting In?”: Recasting the LGBTQ+ Narrative

“Coming Out?” vs. “Letting In?”: Living & Sharing Truth

Support Hotlines

The Trevor Project: (866) 488-7386

The LGBT National Hotline: (888) 843-4564

The Transgender Crisis Hotline: (877) 565-8860

National Suicide Prevention Lifeline: 988

Question Persuade Refer

READ FIRST: Suicide is a difficult topic for many to talk about. If you have lost someone to suicide or have been suicidal, you are welcome to skip to the QPR section for prevention training. If at any point reading you experience any extreme emotions, thoughts, or behaviors, please call or text 988 and talk with a trained professional.

The more awareness we bring to suicide, the less darkness it has. And the less darkness it has, the less power it holds. Talking about it is difficult. But not talking about it is dangerous and deadly. Learn to respond when your friend is in trouble. Learn to react when no one else can. Learn to be the light shining in someone else's darkness so that we can help people have power over their mental health.

Why are people suicidal?

Most individuals who have made a serious suicide attempt and survived don’t truly want to end their life. If they don’t want to end their life, this suggests that there must be underlying reasons. There are two main reasons that have been studied that influence suicidal behaviors: Pain and isolation. Pain can take form in multiple ways including guilt, shame, remorse, unworthiness, addictions, substance use, etc. Isolation, especially within the LGBTQ+ community can look like rejection, disowning from family members, or lack of community.

Three feelings have also been studied that when blended together, the likelihood of suicidal thoughts are very high.

When the person feels unlovable

When the problem feels unsolvable

When the pain has grown unbearable

Warning Signs

80-90% of people who have died by suicide indicated warning signs before taking their life. I often hear people who have lost someone to suicide say “I didn’t think it was that bad” or “I didn’t think they were really going to do it.” Pay attention. Some of these signs may be easy to dismiss as attention seeking. If someone is seeking attention in this way, they need help. Other signs can easily be missed. Suicide is preventable and it may only take one positive action to save a life. Please pay attention.

Direct Verbal Cues:

I wish I were dead

I’m going to end it all

If___ doesn’t happen, I’ll kill myself

Indirect Verbal Cues:

I just want out

I won't be around much longer

I’m tired of my life, I just can’t go on

People would be better off without me

Pretty soon, you won't have to worry about me

ASK if you are uncertain about the intentions behind these phrases such as “Tell me more about that” or “What makes you think that?”

Behavioral Cues:

Any previous suicide attempt

Acquiring a gun or stockpiling pills

Putting personal affairs in order. For example; Receiving a random phone call from a friend thanking you for being there for you in high school

Giving away prized possessions. For example; Your friend gave you his favorite watch

Sudden interest or disinterest in religion

Unexplained anger, aggression, or irritability

What is QPR?

QPR stands for Question, Persuade, and Refer. It is a tool used to reduce suicidal behaviors through practical and proven suicidal prevention training.

Question the person directly about suicide

The fact that you ask is more important than how you ask it. If you cannot ask for whatever reason, find someone who can. Ask with respect. Remember that their life is the most important issue at hand. This is not about you and your feelings. This is about them and their safety. Do not bring up politics or beliefs. Don’t criticize or belittle them for being suicidal. Your job is to ask the question, listen, and let them talk freely. If they do not want to talk in depth about their experience, leave this up to a trained professional.

Indirect: Have you been unhappy lately?

Direct: You seem really sad lately and you matter to me. When other people go through these things its not unusual to have thoughts of suicide. Are you having these thoughts?

Persuade the person to seek and accept help

Listen for protective factors. Examples of protector factors include family, friends, responsibilities, hobbies, important people, religion

Affirm protective factors. What are sources of hope for them? Get them to talk about anything that they care about and affirm it. This will bring them back to the present and give them control.

Script: “You have a dog? I didn't know you had a dog. What kind is he?” or “I didn’t know you played guitar. What kind of music do you like to play?’

Point them towards hope when you sense those emotions deescalating

Script: “I know you are going through a lot right now but it seems like you still have some things that you care about and people who matter to you. Maybe it’s worth staying alive for now.”

Listen and Affirm if the emotions are not deescalating

Refer the person to appropriate resources

Best option: Take the person directly to someone who can help and stay with them

Second option: getting a commitment from them to accept help, then making arrangements

Third option: getting a commitment to not attempt or complete suicide and give the person referral information

If this is a situation where there is a firearm or the person is agitated, call 911. Always put your safety first.

Myths:

Myth #1: No one can stop suicide, it is inevitable

Fact #1: If the person gets help, they may never be suicidal again. Almost any positive action may save a life

Myth #2: Confronting a person about suicide will increase their risk of suicide

Fact #2: Asking someone directly lowers anxiety, opens communication, and decreases risk

Myth #3: Only experts can prevent suicide

Fact #3: Anyone can help stop suicide. Almost any positive action may save a life

Myth #4: People who talk about suicide will not do it - they are looking for attention

Fact #4: If someone is so badly needing attention that they are talking about suicide, give them attention. Ignoring them increases their risk of pain and isolation

Resources for LGBTQ+

National Suicide Prevention Lifeline LGBTQ: Call (press 3) or text (Q) to 988

National Suicide Prevention Lifeline: Call or text 988

Network 180 Crisis Line: 616-336-3909

Arbor Circle: 616-451-3001

LGBT National Hotline: Call 888-843-8564

LGBT National Senior Hotline: Call 888-234-7243

The Trevor Project: Call (866-488-7386) or text (start) to 678-678

Trans Lifeline: Call (877-565-8860)

MI211: Call 844-875-9211 or text 898211

For more information regarding content, please visit:

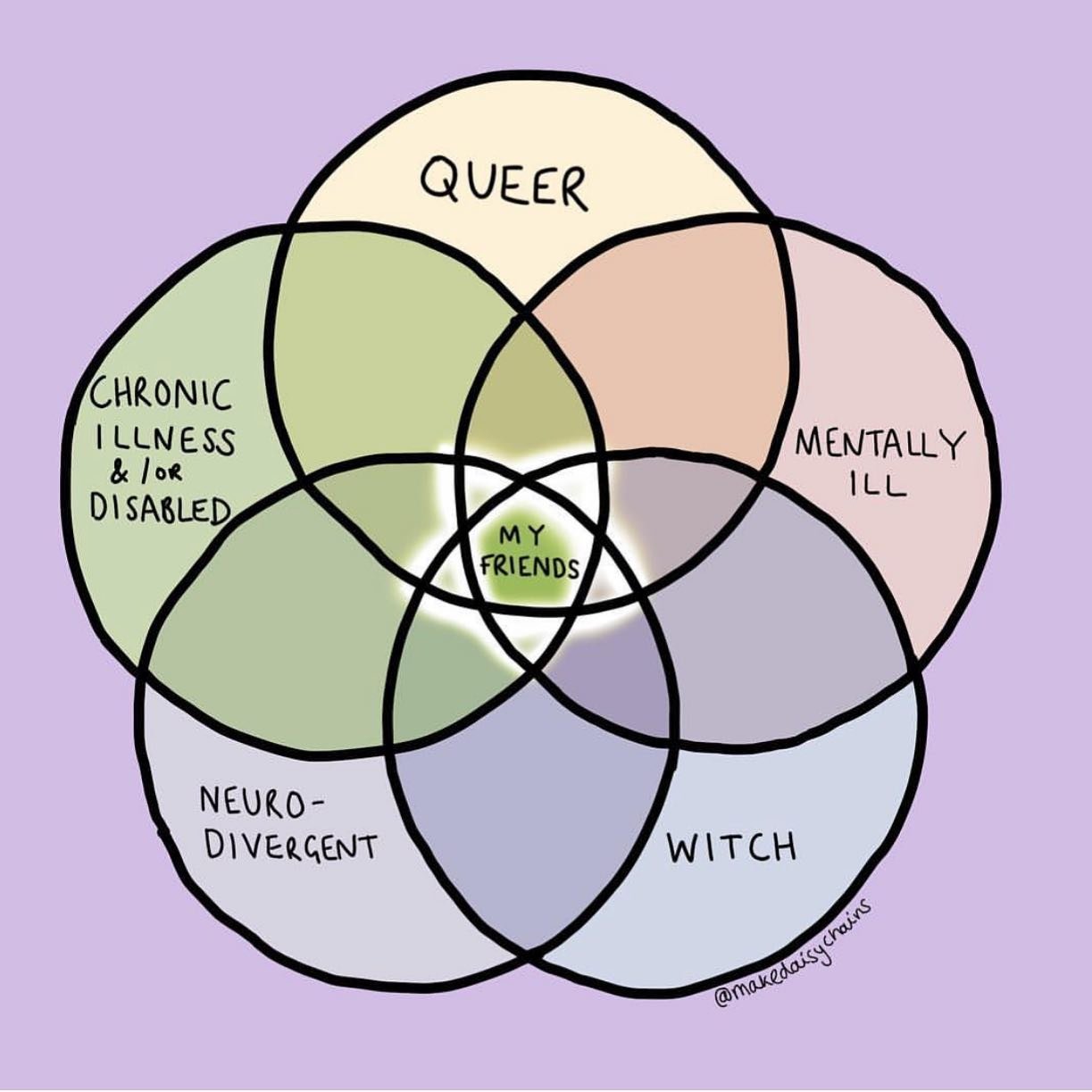

LGBTQ+, Disabilities, and Healthcare

While any LGBTQ+ community member can have any type of disability, one study from the Trevor project highlighted common disabilities among LGBTQ+ young people ages 13-24. In their study, nearly 1/3rd (29%) of LGBTQ+ young people identified as someone with a disability. Below are some statistics on the breakdown of these disabilities:

Mental Health Disorder: 72%

ADHD: 48%

Developmental/Learning Disorder: 32%

Physical Disability: 28%

Autoimmune Disorder: 10%

Oppositional Defiant Disorder: 3%

In comparison, 8% of the general population of young people ages 18-35 report having a disability. Cognitive disabilities were the most common at 10%. It’s important to note that research is still ongoing so these statistics may not fully be developed.

Access to healthcare has been a challenge for both LGBTQ+ people and people with disabilities. For people with disabilities, an inaccessibility to healthcare facilities, equipment, and transportation can be common. Additionally, healthcare professionals caring for people with disabilities may have knowledge gaps about language and specific healthcare needs. Similarly to people with disabilities, knowledge gaps may occur in healthcare professionals caring for the LGBTQ+ community. With these two intersectionalities, healthcare professionals should seek to learn how to best care for this community. Here are some examples of language usage for people with disabilities:

Use person first language. A person with disabilities is an individual before their disability. For example; say “a person who uses a wheelchair” instead of “wheelchair bound” or “a person with disabilities” vs “a disabled person.”

Use identity first language when preferred by the individual. This language is used as a reclamation of disability identity and indicates disability pride. It is most common for autistic people and people in the deaf community but can encompass other disabilities depending on the individual. For example; say “Autistic person” rather than “a person with autism.” Always ask before using identity first language.

Avoid ableist language such as “stupid,” “crazy,” “dumb,” “crippled,” “lame” or phrases such as “I’m OCD about…”

Having healthcare providers understanding and addressing healthcare gaps builds credibility with LGBTQ+ people with disabilities. One survey concluded that 72% of LGBTQ+ people with disabilities avoid discussing their LGBTQ+ identities with their healthcare providers with 9.8% never having disclosed their LGBTQ+ identities. Reasons indicated included negative interactions (fear, distrust, avoidance of care) at 40.1%, dismissal/denial of treatment at 30.5%, and assault/aggressive activity at 4.1%. It is important to disclose this information to a trusted healthcare provider, given that it is a safe space to do so, in order to keep in good health. Benefits of disclosing this information include caring for needs specific to identity, using preferred names/pronouns, and providing additional support for the individual or family members.

Here are some Action Steps for healthcare providers to help build trust:

Ensure that medical equipment is available to people with disabilities such as scales, examination tables, or chairs

Plan for additional time during exams

Communicate on the patients level wherever that may be. Make sure the person is understanding what you are saying. If you are unsure of what they are saying, repeat back what you heard

Always treat the person with a disability as an independent individual. If the person has someone with them for interpretation purposes, still speak directly to the person rather than the interpreter.

Don’t assume that they need help. Always ask before helping or initiating physical contact.

When addressing someone using a wheelchair or other mobility device, offer to shake hands as you would with anyone else and make eye contact at the person’s level.

Free Webinar

Trauma Informed Care

What is trauma?

“Trauma results from an event, series of events, or set of circumstances that is experienced by an individual as physically or emotionally harmful or life threatening and that has lasting adverse effects on the individual’s functioning and mental, physical, social, emotional, or spiritual well-being” (SAMHSA, 2014, p. 72 ) In other words, trauma can be understood as any extraordinarily stressful experience in life that has a lasting negative impact on someone.

What is Trauma Informed Care?

A trauma-informed approach to the delivery of behavioral health services includes an understanding of trauma and an awareness of the impact it can have across settings, services, and populations. It involves viewing trauma through an ecological and cultural lens and recognizing that context plays a significant role in how individuals perceive and process traumatic events, whether acute or chronic. Trauma Informed care looks at the person as a whole instead of just physically or mentally.

The Neurobiology of Trauma

Trauma Informed care looks specifically at adaptation or how the nervous system is constantly adapting to how the nervous system responds. When an extraordinarily stressful event happens, the brain can store that information. When the event is over, your brain continues to react to the information as if you are still in danger. Brain areas implicated in the stress response include the amygdala, hippocampus, and prefrontal cortex. There are five types of stress responses which can vary depending on the person and situation. These types include:

Fight happens from the waste up. Muscles tense up and fists/jaws can clench. Feelings can include wanting to punch or yell in order to get out of the situation.

Flight happens from the waste down. Legs can be tense and muscles contract. Feelings can include wanting to run or having restless legs.

Freeze happens from head to foot. You can’t respond or move. From an evolutionary perspective, this is helpful to blend in with the surroundings

Fall happens when the body becomes physically or mentally unresponsive. Fainting may happen. From an evolutionary perspective, the body preserves energy

Fawn is the drive to appease the aggressor. This response happens in the prefrontal cortex because it takes a lot of thinking to not say the wrong thing

What does trauma in the LGBTQ+ community look like?

Trauma in the LGBTQ+ community is similar to trauma faced in other populations.The biggest difference is that it's magnified because not only is the bad thing happening but the bad thing is happening because of being LGBTQ+. Some common themes surrounding the LGBTQ+ community found among mental health therapists include:

Religious trauma

Conversion therapy

Stigma surrounding what a marriage should look like

Toxic relationships

Boundary crossing

Difficulty identifying toxic relationships

Family relationships

confusion around people who are “accepting” but not accepting

Toxic family dynamics

What does trauma informed care in a healthcare setting look like?

There are several domains in which the approach to Trauma Informed Care can be applied to. These domains include:

Safety (Physical, Psychological, Emotional)

Be aware of your body language with a patient – don’t tower over patients or visitors, allow a patient an option of where to sit in the room so that they may see and access the door.

Trustworthiness and Transparency

Let patients know which parts of the body may be impacted before beginning or proceeding with an exam. When possible, allow patients more control of care steps, i.e. apply gel, holding a stethoscope.

Collaboration and Mutuality

Learn about patient strengths and resources to manage past challenges. Ask “what has worked for you in the past?”

Empowerment, Voice, Choice

Provide options wherever possible: - Doors, curtains, shades – can the patient decide if they want those open or closed? - If a patient has to be woken up for meds or vitals, ask how they would prefer to be woken up. - Conduct as much of the visit with a patient’s own clothes on rather than dis-robing.

Recognition of Cultural, Historical and Gender Issues

Use interventions that respect diverse cultural backgrounds and create opportunities for patients to engage in culturally sensitive interventions and practices that promote trauma healing and recovery.

Peer Support

Promote healing and recovery by valuing lived experience of patients and individuals with shared experiences. For example, create mutual support groups for patients and offer peer supporters/navigators as part of health care delivery.

A full comprehensive list can be accessed here

Pride Month

Why do we celebrate pride?

Before Stonewall, "Reminder Day Pickets" took place in order to regain the rights to work for the government. Many LGBTQ+ people were fired due to their sexual orientation so silent protests were held every year in hopes to gain this right back. With oppression still continuing, a riot eventually broke out at the Stonewall Inn on June 28th, 1969. Protesting and riots continued for 6 more days. This served as a catalyst for the Gay Rights Movement. Yearly marches were then held to commemorate stonewall. Watch this video to learn more about the events leading up to Stonewall.

What does pride mean?

The word “pride” can be broken down into two different facets: Authentic and hubristic. Hubristic pride is defined as having an excessively high opinion of oneself with egoistic and arrogant characteristics. This type of pride is unhealthy because it is associated with aggression and relationship dissatisfaction. Authentic pride includes satisfaction taken in an achievement, possession, or association. This type of pride is the more common understanding in reference to pride month. Pride month is a commemoration of Stonewall and the progress of LGBTQ+ individuals. This is authentic pride because it involves a satisfaction of achievement and association to a larger group - and this is something to celebrate! For example; Someone may say “I am proud to be part of a community who values and respects who I am.” This is what pride month is all about - a celebration of authenticity, diversity, and togetherness.

Why is having pride important?

Authentic pride (in moderation) is very important. This type of pride can be healthy because it can encourage us to succeed and promote prosocial behaviors. In terms of mental health, pride can have many benefits including high self esteem, self worth, confidence, and sense of accomplishment. However, moderation is the key. One quote based off of Aristotle explains this:

“Too little is failing to acknowledge what has been achieved—a form of false humility—and too much is vanity.”

Pride Events:

Grand Rapids

Date: June 22

Learn more: Grand Rapids Pride Center

Detroit

Date: June 8-9

Learn more: Motor City Pride

Lansing

Date: June 22

Learn more: Lansing Pride

Holland

Date: June 29

Learn more: Out On The Lakeshore

Muskegon

Date: June 1 at 10:30

Learn more: Muskegon Pride

Grand Haven

Date: June 8

Learn more: Grand Haven Pride

Autistic Adults

How are autistic characteristics in adults different?

Autistic characteristics in adulthood may look differently than in childhood. Characteristics that are more common in adulthood may include:

Difficulty in understanding other people's thoughts or emotions

Anxiousness in social situations

Difficulty in making friends or preferring to be alone

Sounding blunt, rude, or uninterested in others without intending to

Difficulty in explaining feelings

Taking words or phrases literally

Having the same routine and feeling distressed if the routine is not followed

Other characteristics may include:

Not understanding social rules

Avoiding eye contact

Getting too close or getting upset if others get too close

Noticing details, patterns, smells, or sounds if people get too close

Having a keen interest in certain subjects or activities

Planning things before doing them

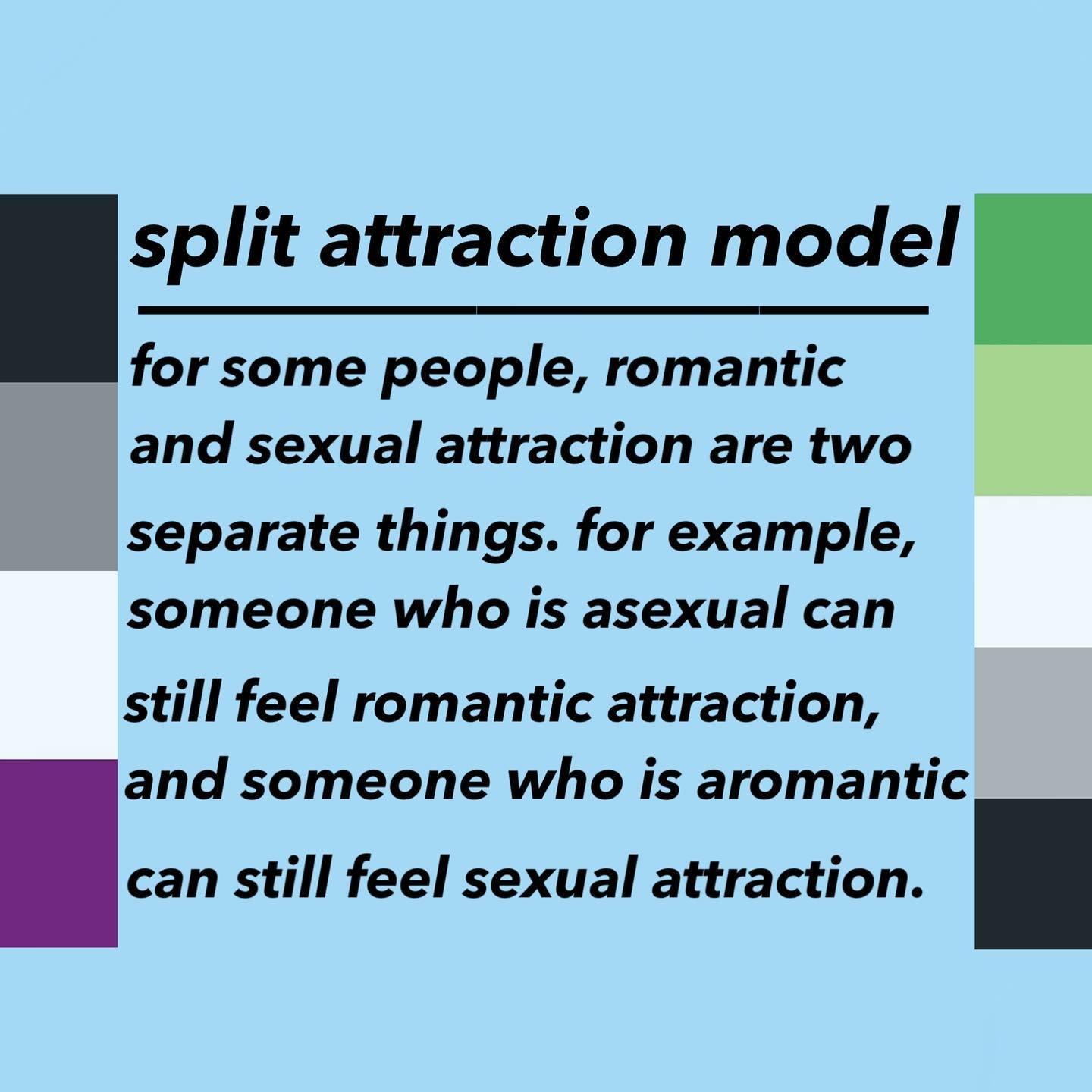

autism and queerness

The largest study on sexual activity, orientation, and health of autistic individuals reaffirms previous research that autistic individuals are more likely to have a wider range of sexual orientations than non-autistic individuals. The results from this study reveal that autistic people are 7-8 times more likely to identify as asexual or non-heterosexual orientations. It is not very understood as to why this is.

Words of the Autistic community:

Neurotypical - an informal term used to describe a person whose brain functions are considered usual or expected by society. (Rudy,

Neurodiverse - refers to differences in brain function among people diagnosed with an autism spectrum disorder (ASD)

Neurodivergent - describes someone who isn't neurotypical

Meltdown - Having extreme reactions to specific situations. When someone is overstimulated, they may lose behavioral control. This can look like crying, shouting, laying on the floor, and sometimes engaging in dangerous behaviors such as self-injury or aggression.

Sensory Processing - sensory problems relating to sights, sounds, smells, taste, touch, balance, and general body awareness. There are two types of sensory processing: Hypersensitivity (over-responsiveness) and hyposensitivity (under-responsiveness).

Stimming (self-stimulatory behavior)- specific, repetitive behaviors that can include hand-flapping, rocking, spinning or repetition of words and phrases

Preservation - repetitive or persistent action or thought, after the stimulus that prompted it has ceased. The person may have difficulty shifting gears.

Masking - camouflaging autistic characteristics

For more words, click here

Autistic Assessments:

If you think you might be autistic, talk to your doctor or therapist if you would like to receive an Autism Assessment. An assessment may help you to understand why you might find some things harder than other people, explain to others why you see and feel the world in a different way, and get support at college, university or get some financial benefits. Before your assessment, Here are some ways you can prepare:

Write a list of the signs of autism you think you have and bring it with you

Ask people who know you if they have noticed any possible signs

If helpful, bring someone with you who knows you well

Purple Ella

Purple Ella is Autistic, ADHD, nonbinary, content creator, and advocate. Check out their video about their experience with the Adult Autism Assessment:

Empowering Survivors of Domestic Violence

What is Domestic Violence?

Domestic violence is defined as “a pattern of abusive behavior that is used by an intimate partner to gain or maintain power and control over the other intimate partner” (Domestic and Dating Violence, n.d). It can be any action that is physical, sexual, emotional, economic, or psychological. Behavioral intentions can be to intimidate, manipulate, humiliate, isolate, frighten, terrorize, coerce, threaten, blame, hurt, injure, or wound someone.

Domestic Violence in the LGBTQ+ Community

Domestic Violence in the LGBTQ+ community can be experienced at the same rate in similar ways as non-LGBQT+ people. However, different obstacles may impact the LGBTQ+ community.

Fear of Isolation - many community members belong to families with traditional values, oppressive living environments, or religious communities. The abuser may use this isolation and have the person be more dependent on them

Shame of Identity - the abuser may play into the person's internalized homophobia and shame them for their pronouns or chosen name. The abuser will use power and control to keep the person in isolation

Fear of not receiving services - In the LGBTQ+ community, minimization of domestic abuse can happen meaning that others might not view domestic abuse in the LGBTQ+ community as legit.

Variation of legal protection - receiving legal resources for domestic violence can vary depending on the state. Impact and state reports can be found here.

What to do if you know of someone experiencing Domestic Violence

If you know of someone who is in a domestic violence situation, it’s important to consider the wants and needs of the person in the situation. They may or may not have acknowledged that they are in a bad situation. Until they acknowledge this and want help, honoring their wishes and boundaries is important in establishing yourself as a safe person. Below are several steps you can take to help:

Ask them what they want - Is there some way you can support them?

Document the abuse every time you hear about it

Create a safety plan with the person experiencing abuse if they are ready

Knock on their door to make an excuse of why you are there as a way to interrupt whatever is happening

“I just ran out of eggs. Do you have any I can use?”

Reach out to the YWCA if you need additional support

Call: (616) 454-9922

Location: 25 Sheldon Avenue SE Grand Rapids MI, 49503

How the YWCA is addressing Domestic Violence

Jenna Schook, the Volunteer Advocate Program Manager, enjoys connecting with survivors when they come in. The YWCA provides services for survivors of domestic violence and dating abuse. The organization is unique in having a Nurse Examiner Program that provides medical forensic exams at no cost.

When a survivor reaches out to the YWCA, they will first talk to a nurse to schedule an exam. During the appointment, they will meet with an advocate (emotional supporter) and nurse while talking over any questions or concerns. A survivor has control over how the exam will go. Nothing is going to happen without the consent of the survivor. If the survivor chooses to give consent to having the full exam, the following steps will take place:

History about the details of the assault or abuse that took place

Physical exam

Discussion over possible medications, safety planning, or different resources

Volunteer with the YWCA

Volunteer Advocates are people who walk alongside survivors throughout the entire process. While anyone who is interested in being a volunteer is encouraged to reach out to the YWCA, volunteers within the LGBTQ+ community are needed. Volunteers within the reflected communities can experience a special connection with survivors that those outside of these communities cannot make. Additional healing and comfort can arise from survivors being matched with someone who reflects their unique identity.

Some essential duties for volunteer advocates include answering helpline referrals when a sexual assault call is made and being in the exam room with the survivor when the nurse calls. Volunteers can generally expect to be on call for one 12 hour shift. Around the holidays, volunteers can expect two 12 hour shifts. If you are interested in being a volunteer, reach out to Jenna Schook at jschook@ywcawcmi.org or go to the YWCA website and fill out an application.

Lgbtq+ specific Resources

Domestic Abuse and its impact on Transgender and Nonbinary Survivors

LGBTQ+ Sexual Violence Prevention and Response Toolkit

Am i experiencing domestic violence

Cervical Cancer Awareness

What is Cervical Cancer?

Cervical cancer is cancer that starts in the cells of the cervix. First, abnormal cells appear in the cervix and go through a process called dysplasia. If left untreated, the cells develop over time and become cancerous, potentially infecting the surrounding area.

What does screening look like?

Depending on the age group, screening is highly encouraged for people with a cervix every 3-5 years. During screening, a pap test is used to collect cells from the cervix which are then examined to determine if the cells are cancerous. Since anxiety is common with these types of exams, options such as being put under or a self pap may be offered.

Concerns about the LGBTQ+ community relating to care

There are many concerns regarding healthcare experiences within the LGBTQ+ community. Suzanne West, an OBGYN, is an affirming provider in the Grand Rapids area who voiced her concern. Her primary concern is that the community is at greater risk for cervical cancer due to the avoidance of care. When screening for cervical cancer becomes a regular routine, cervical cancer is 100% preventable. In fact, cervical cancer screening decreases death by 50%. If the avoidance of care remains unaddressed, the LGBTQ+ community will continue to be at an increased risk. This will have to be a community effort to better educate and equip our healthcare professionals in their understanding of LGBTQ+ Identities.

Why do LGBTQ+ community members tend to avoid care?

According to one study, 1 in 6 LGBTQ+ individuals reported avoidance of healthcare due to anticipated discrimination. To gain insight as to why this is, Suzanne West was asked this question. When asked this question, she stated a couple of reasons for the tendency to avoid care:

Negative experiences or poor treatment from healthcare workers

LGBQ: 6% of health care providers refused to see them due to sexual orientation

Transgender: 29% of health care providers refused to see them due to gender identity

2. Lack of financial support

44% of LGBTQ+ people ages 18-64 were earning less than $13,590 (per individual) per year in 2022. That’s 200% of the federal poverty level

How can healthcare providers adapt to the language for them to feel comfortable?

Healthcare providers can decrease negative experiences with healthcare by adapting the language that is used with patients. For people who have a different gender identity, using less gendered terms may reduce fear. Below are some tips on how language can be addressed:

Use less gendered terms

Example: “Exam” rather than “Vaginal Exam”

Ask: What language would you like me to use to describe your results?

2. Remove fear of the exam

Show equipment used

Communicate simple explanations

3. Use proper names and pronouns

Double-check forms to ensure accuracy

4. Educate yourself about LGBTQ+ language

LGBTQ+ Youth: Unsheltered and Unstable housing

Note: the term “unhoused” is sometimes used in replacement of “homeless.”

According to multiple sources, LGBTQ+ youth are disproportionately impacted by homelessness (Choi, Wilson, Shelton, & Gates, 2015; Durso & Gates, 2012; Morton, et al., 2018; Baams et al., 2019). True Colors United estimates that 7% of US youth are LGBTQ+ while 40% of LGBTQ+ youth are unhoused. This proportion means that LGBTQ+ youth are nearly five times more likely to experience unstable housing or homelessness than the general population. There are four main factors contributing to this overrepresentation:

Family Conflict

According to The Trevor Project, 14% of LGBTQ+ youth were kicked out or abandoned. 40% of those instances were due to sexual orientation or gender identity. 16% of LGBTQ+ youth ran away. 55% of those instances were due to mistreatment or fear of mistreatment due to sexual orientation or gender identity.

Aging out of Foster Care

LGBTQ+ youth who reported past housing instability or are currently unhoused had nearly 6 times greater odds of reporting that they had been in foster care at any point in their lives.

Poverty

Overall, the LGBTQ+ community is more likely to experience poverty than cisgender and heterosexual people. Looking at data from 2020, 23% of LGBT people lived in poverty compared to 16% of non-LGBT people.

Shortages of Shelters and Housing Programs

On any given night in Michigan, there are 8,206 people who are unhoused. While there are 184 homeless shelters in Michigan, there would have to be about 45 open beds in each of these shelters to house all of these people.

Watch this video to learn more about LGBTQ+ youth who are unhoused and how you personally can make an impact.

While many policies in Michigan have been put into place for LGBTQ+ acceptance, there is still much work to be done across the US. Policy change against systematic oppression is needed in order to eliminate youth who are unhoused in the LGBTQ+ community. Here are some recommendations from Mel Moore, an activist, on how policy can help eliminate barriers:

Social support instead of criminalization for life sustaining activities out in public. According to the National Coalition for the Homeless, criminalization activities may include:

Confiscating personal property (tents, bedding, medications etc.)

Criminalization of panhandling (begging for money)

Criminalization for publicly sharing food with the homeless

Enforcing a “quality of life” ordinance relating to hygiene

Research suggests that 48 states in the US has at least one law criminalizing homelessness activities. If we truly want homelessness to be resolved, a focus should be placed on how to provide housing and stability rather than criminalization of life sustaining activities.

Ban conversion therapy in all states. Currently, 22 states have a ban on conversion therapy. Conversion therapy is the attempt to change one’s sexual orientation to straight or one’s gender identity to cisgender. Studies have not shown conversion therapy to be effective but have proven this therapy to be very harmful. Watch this video to learn more about conversion therapy. Conversion therapy can contribute to family conflict, which can lead to further stigmatization and unsafe home environments.

Support organizations that advocate for policy change to end homelessness at the local, state, or global level. Below are a list of advocacy organizations:

Kent County: Coalition to End Homelessness

Michigan: Michigan Coalition Against Homelessness

United States: National Coalition for the Homeless National Runaway Safeline

LGBTQ+ Specific: True Colors United Chosen Family of West Michigan

Resources

How can I help?

Do you need help?

National Homeless Shelter Directory

Locate a Homeless Youth Shelter

Concerned Adults

Service providers

Intersex Identities

The term Intersex refers to a person who has variations of male and female physical, hormonal, or genetic sex traits which can appear at birth or later in life. Intersex people are estimated to be born in approximately 2% of live births.

There is much debate over the ethical practice of surgical intervention for intersex infants. Historically, intersex individuals have been considered “abnormal” and in need of fixing regardless of whether or not the treatment was medically needed. This idea stemmed from John Hopkins University in 1950 when they introduced the “Optimum Gender of Rearing Model.” With this model, typical gender upbringing was emphasized and genital surgeries were highly encouraged for intersex infants. According to the American Academy of Family Physicians, genital surgeries should only be recommended if it “[resolves] significant functional impairment or reducing imminent and substantial risk of developing a health- or life-threatening condition.” While surgeries are necessary in some cases, it’s critical to acknowledge the potentially harmful impacts that medically unnecessary surgery can have. It’s important to take note that forgoing unnecessary medical surgeries on infants have no evidence of having psychosocial problems later in life. Especially since the intersex individual can choose to receive these surgeries when they are old enough to consent. Surgeries impacting the genitalia may have negative irreversible effects such as “infertility, chronic pain, inaccurate sex/gender assignment, patient dissatisfaction, sexual dysfunction, mental health conditions, and surgical complications.” One medical personnel shares their insights:

“They [intersex people] get tired [of the entire situation]. Generally, when we see them here it is for another reason or for a complication. They are patients who have been seen and treated many times. They are not coming for a follow up. They don’t want to know anything. They’ve had surgeries, disorders of their sexuality. They don’t have a sex life. They’re not interested because there’s pain, they don’t feel much pleasure, and also because of the surgeries, which are not harmless: they cause adhesions or scar-like tissue, they have abnormal wound healing and [result in] many complications… they don't end up the same.” (Interview 5: medical personnel)

Further supporting this insight, The World Health Organization, American Academy of Pediatrics, twelve United Nations agencies, and several other organizations denounced early genital surgeries from 2010-2017. Although several organizations highly discourage this practice, medically unnecessary genital surgeries are still legal today in the US and may be practiced by medical professionals. Watch this video about how these irreversible surgeries impact the lives of children and their surrounding loved ones.

Resources

for the intersex community

Seeking Medical Care as an Intersex Person

For parents of intersex children

How To Retrieve Medical Records

Know Your Rights: A guide for parents

for medical providers

Ethical Guidelines for Intersex Surgeries

Intersex Affirming Hospital Policies

Affirming Primary Care for Intersex People

advocacy and support groups

learn more about the intersex community

The Do’s and Don’ts of Being an Ally

Watch Every Body Movie trailer

Read XOXY: A Memoir (Intersex, Woman, Mother, Activist) by Kimberly Zieselman

Legislative Toolkit: How to create change in your state

LGBTQ+ US Military History

History reveals where we have walked and where we have yet to travel. LGBTQ+ people have stumbled over rocks and trudged through mud all while dodging tree branches that seemingly never fail to swing towards them. LGBTQ+ military folks in particular may be familiar with these kinds of struggles, not only from bootcamp, but by oppression from the military throughout history. With currently 6.1% or 1.3 million LGBTQ+ members serving in the military, various policies have impacted the environment for those serving.

Check out this timeline of LGBTQ+ US military history overview as we conclude LGBTQ+ History Month and approach Veterans Day this November.

1953

Executive Order 10450 implied the ban of LGBTQ+ people in the military by using the phrase “sexual perversion.” The phrase “sexual perversion” was used to describe those who were not allowed to be employed by the government which led to 7-10,000 lost jobs. The number of people released from service due to sexual orientation is unknown.

1982

A Department of Defense policy was enacted stating that “Homosexuality is incompatible with military service.” This policy prohibited service for those who “engages in, desires to engage in, or intends to engage in homosexual acts.” This was a more specific ban on LGB people most likely due to an increase in community awareness of the LGBTQ+ movement.

1993

The Don’t Ask Don’t Tell Policy was enacted which allowed gay, lesbian, and bisexual people from serving as long as their identity remained unrevealed. It is estimated that between 14,000-43,362 of gay, lesbian, and bisexual people were discharged from the military due to this policy. Factors such as fear, imbalance of power, retaliation, and trauma likely influenced this wider range.

2011

The Don’t Ask Don’t Tell Policy was repealed through former president Barack Obama. Gays, lesbians, and bisexuals were able to serve openly in the military. Although the repeal was a great start, there was still a lot of progress to be made with homophobia in the military. Watch how this policy impacted the LGB population.

2013

The Department of Defense implemented Survivor Benefit Coverage to same-sex spouses of military members and veterans. Official document explaining benefits can be found here.

2016

Transgender people are finally able to serve… well kind of. For all transgender people with no diagnosis of gender dysphoria, they were allowed to serve only in their sex assigned at birth. For current service members, they were only able to serve if fully transitioned. For new applicants with a diagnosis or history of gender dysphoria, or if they had a history of medical transition treatment, they were only allowed to serve if they had been transitioned for 18 months. The reasoning behind the specific rules involves physical transitioning may involve more extensive accommodations than the government was able to provide. For further clarification, see this chart. This content may contain culturally inappropriate language.

2018

Enacted by former President Trump, transgender people were banned from the military unless they were diagnosed with gender dysphoria before 2018 and/or willing to stay in their sex assigned at birth. This meant that anyone who was in transition, who had transitioned, or who was “unstable” in their sex assigned at birth could not be in the military. This ban impacted thousands of transgender people already in the military. Watch how the impending band impacted military members.

2021

The transgender ban was reversed by president Biden allowing transgender individuals and those with gender dysphoria to serve openly in the military. The following provisions were added:

The military provides a process for people to transition while serving

A service member may not be discharged due to gender identity

The military has a procedure for changing a service member’s gender marker

Veteran Healthcare Resources

How to add/change gender or name on va.gov

Veteran Sexual Health and Sexual Orientation

Veteran Health Care for Gay, Bisexual, and Queer Men

Veteran Health Care for Lesbian, Bisexual, and Queer Women

Veteran Health Care for Transgender and Transmasculine Men

Provider Resources for LGBTQ+ Veterans

Veterans Health Administration LGBTQ+ Training

CDC TRAIN: LGB Veteran Health Care

CDC TRAIN: Transgender: Older Transgender and Gender Diverse Veteran Care

CDC TRAIN: Transgender: Care for the Gender Nonbinary Veteran

CDC TRAIN: LGB Sexual Health Care for Genderqueer and Nonbinary Veterans

CDC TRAIN: Healthcare Concerns for Older LGB Veterans

The Overlap of Neurodiversity and Queerness

April is Autism Acceptance Month, so for this month’s blog we want to explore the intersection of LGBTQ+ and neurodiversity more generally. In addition, we’re going to share some tips for providers and healthcare professionals on caring for, treating, and plain ol’ interacting with neurodiverse LGBTQ+ patients. Much like other marginalized groups, neurodiverse LGBTQ+ people face unique barriers to care and suffer due to misinformation, discrimination, and medical mistrust. In order to go beyond awareness of Autism and neurodiversity towards acceptance, we must continue learning how to be affirming allies and break down misinformation.

What does neurodiverse mean?

According to Neurodiversityhub.org, “Neurodiversity refers to the virtually infinite neuro-cognitive variability within Earth’s human population. It points to the fact that every human has a unique nervous system with a unique combination of abilities and needs.” Much like how “LGBTQ+” houses a variety of identities under its umbrella, the term neurodiversity covers a variety of neurotypes and variations of the human mind. The neurodiverse umbrella includes Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), sensory processing disorders, tic disorders, and many others.

What is ableism?

Ableism is a system of oppression that operates on the belief that able-bodied, neurotypical people are the norm, that disabled, neurodiverse people are abnormal and are therefore discriminated against. According to the Therapist Neurodiversity Collective, “Ableism is entrenched in the presumption that neurodivergent and/or disabled people are "broken" and need to be ‘fixed.’”