Still Important, just not Romantic

Looking beyond Monogamous, Romantic relationships and the importance of Recognizing significant friendships & Other relationship structures - in honor of AroSpec Awareness week

Graphic made by Arly using Canva, AroAce flag made by aroaesflags

Following Valentines’ Day on February 14th, the 19th-25th is Aromantic Spectrum Awareness Week, a time to spread awareness and acceptance of aromantic spectrum identities and the issues arospec people face, as well as promoting awareness of the existence of arospec folks and celebrating them. As acceptance for non-cishet identities grows, so should the way we view relationships and support networks, expanding beyond monogamous, romantic relationships and biological families.

In the United States, according to the US Government Accountability Office (GAO), there are 1,138 federal statutory provisions where one’s marital status plays a role in determining benefits, rights, and privileges. Same-sex marriage is now included in these provisions, which is seen as a win for LGBTQ rights all across the US. But as we begin to view the myriad of ways that folks can form significant relationships outside of marriage, we can see how marriage is not the end-all-be-all of LGBTQ rights, especially from a patient rights lens. In this blog, we are going to explore a few ways that folks form relationships outside of marriage and why it is incredibly important for providers, other healthcare workers, and society at large to honor these relationships when it comes to medical decision making and support.

To start off, let’s talk more about aromantic and aro spectrum identities. According to aromanticism.org, the term “aromantic” (aro for short) describes someone who experiences little to no romantic attraction. Aromantic people are not broken, mistaken, or “waiting for the right person” and are still capable of establishing significant relationships outside of romance. For example, someone who is aromantic can also be allosexual, someone who experiences sexual attraction. Therefore, from a healthcare perspective, it would still be important to ask the patient whether they are sexually active, the type of sex they are engaging in, number of partners, contraception used, etc. Being educated on the terms that patients can identify as takes the burden of educating the provider off the patient, which is often tiring and stressful for the patient.

As noted previously, romantic attraction is on a spectrum; the way that someone views their identity and forms relationships can exist anywhere along not just the aro spectrum but also the asexual and aplatonic spectrums. If you’re getting a little overwhelmed here with all the spectrums, that’s okay, but it just shows that relationships can form and be experienced in ways far beyond our traditional understandings! With these expanding understandings of romantic, sexual, and platonic attractions, we can begin to see why holding marriage as the ultimate union doesn’t work for some folks.

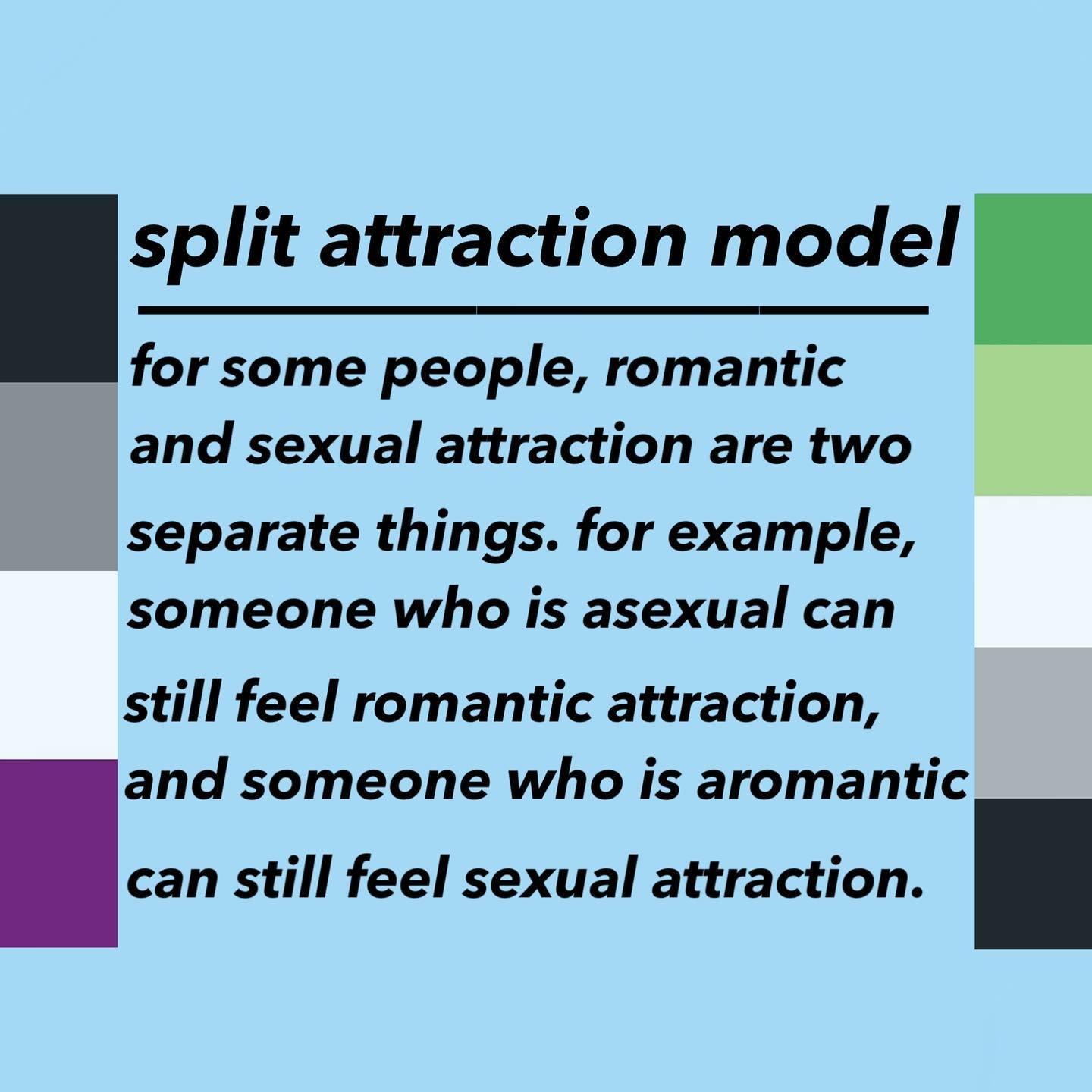

Graphic made by Columbiaces

This idea of separate forms of attraction is known as the Split Attraction Model (SAM), which you can learn more about here. For some folks, the SAM doesn’t really work for them, whether they don’t relate to the language, find it too confusing, or just aren’t a fan of it (learn more here). No matter how someone defines their identity or what labels they use, we must trust that they know themselves better than we possibly could, while also acknowledging that labels can change.

For a great number of LGBTQ+ folks, they don’t have a biological family to rely on for support, which is where found/chosen family comes into play. Whether it’s a young queer teen in need of housing or an elderly trans person in need of home care, found family often provides needed support to survive after facing rejection from one’s biological family. This network of found family should be seen as just as valid as a biological family, as it provides the much needed love, care, and support that may not be guaranteed in one’s biological family. However, laws governing medical decision-making are mainly based on biological and marital relationships (part of the 1,138 federal statutory provisions mentioned above), leading to difficult, even complicated, situations for LGBTQ+ patients without advanced healthcare directives or other documents naming their found family to make decisions on their behalf.

I personally use a wide variety of labels to describe my varied places on the attraction spectrums, as well as my gender identity: pan/demisexual, greyromantic, polyamorous, transgender and non-binary. My parents are not involved in my life and my extended family is supportive but religious with differing views than mine on healthcare; my brother just became a legal adult and is navigating that special brand of chaos; I am not in any significant relationships at the moment; my main supports are my found family of older enbies and fellow Gen Z queers. So where does this leave me should I become unable to make medical decisions for myself? This is a question that myself and many other LGBTQ+ folks are left to ponder -and occasionally, are forced to scramble for answers.Our first pick to be our medical advocate may be unable to do so without proper planning and paperwork beforehand; our (disapproving) families may be the ones who come to our side because they are the only ones allowed to, leading to misgendering, deadnaming, and discriminatory care.

Holding marriage as the highest ideal to aspire to excludes the wide breadth of relationships that we can develop. Relying on only biological or legal families excludes the people in our lives that we hold just as near and dear to our hearts. Having significant relationships outside of romance and/or sex are just as valid and important; aromantics can still desire close relationships and be sexually active. Collecting sexual orientation and gender identity (SOGI) data is not just for data's sake: it is so that providers and healthcare staff can provide culturally appropriate care for their patients and ask relevant questions tailored to each patient’s needs. Medical mistrust and avoidance among the LGBTQ+ community due to discrimination and prejudice (anticipated or past experiences) means that preventable and treatable issues go untreated, leading to poor physical and mental health. Respecting the patient/person, as well as the terms and labels they use to describe themselves is a way to support mental and physical health; by fostering an affirmative, caring, trauma-informed environment, patients can feel comfortable enough to receive the care they need.

If you’d like to learn more about aromantic spectrum and other identities, check out the videos linked throughout the blog.